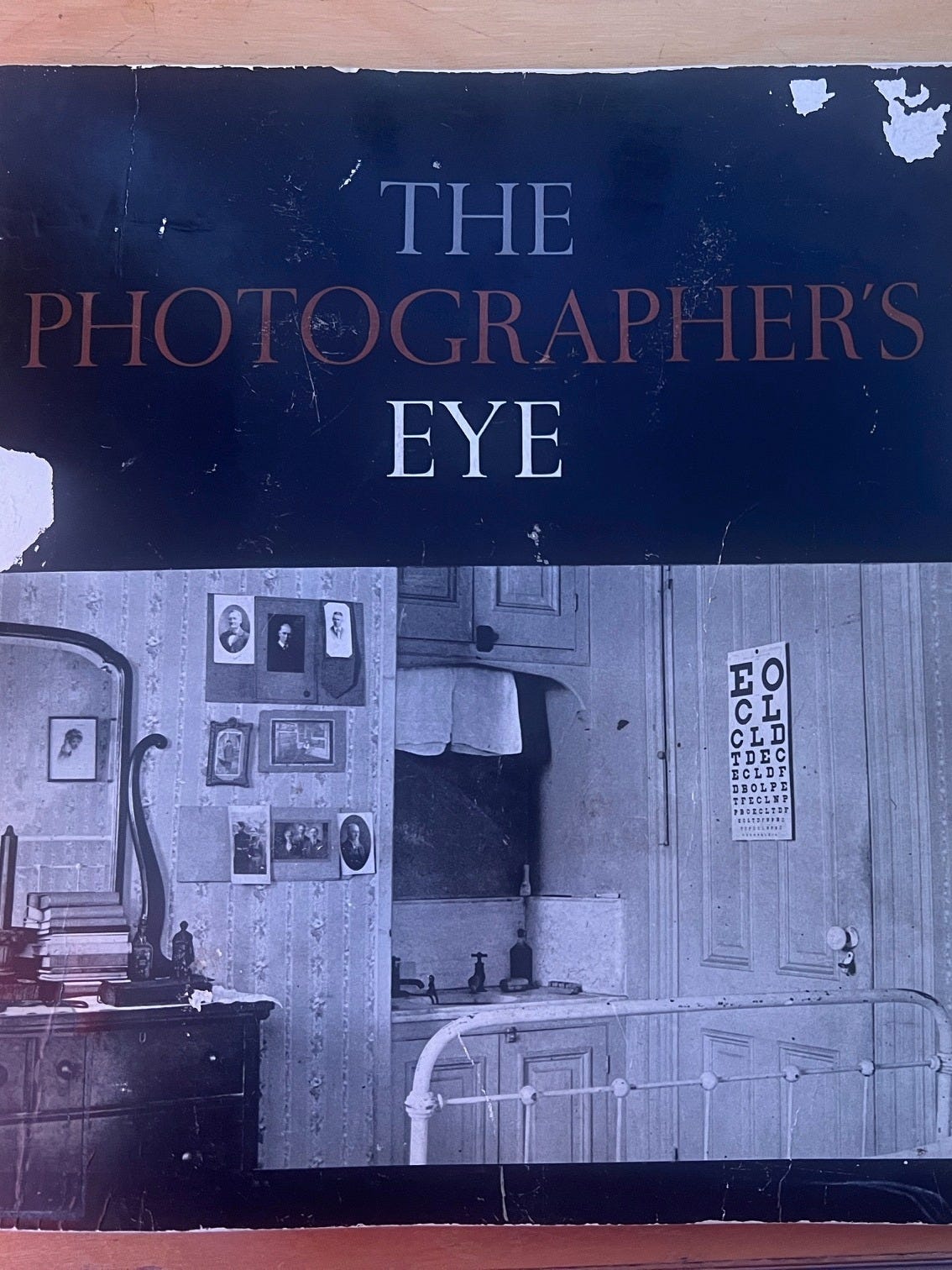

The Photographer's Eye

by John Szarkowski

Greetings, folks,

I hope everyone’s well and enjoying the days.

Browsing in our college library for the hidden truths of the universe, I stumbled upon a book that hasn’t been checked out in 27 years — The Photographer’s Eye, by John Szarkowski. Guess I too might have a photographer’s eye after all.

John Szarkowski (1925–2020) was a highly influential photography curator, critic, and historian. He served as the Director of Photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York from 1962 to 1991. When he talked, people listened.

According to Szarkowski, “paintings were made – constructed from a storehouse of traditional schemes and skills and attitudes – but photographs, as the man on the street put it, were taken.”

Szarkowski’s distinction between painting and photography highlights a fundamental difference in how these two visual arts are created.

Paintings are are built layer by layer with intentionality, using established artistic conventions, techniques, and compositions. The painter begins with a blank canvas and applies colors, shapes, and forms according to their vision. This process allows for total control over every element within the frame.

In contrast, photographs are taken, meaning they involve capturing something that already exists in the world. The photographer does not create the scene but instead selects and frames a moment from reality. The act of taking a photograph involves recognition rather than invention—an ability to see and extract meaning from what is already present.

Is “taking” on the same level of artistic expression as “making? I posed this question to Dr. Scott Weiss, a scholar of East German cinema and an amateur photographer himself. “Just as a brilliant piano performance can be as moving and artistically significant as an original composition, a masterful photograph can be as impactful and artistically valuable as a painting,” replied Weiss as if he’d thinking about it all his life. And maybe he had. I promised to buy him a beer in a plastic cup and we went our separate ways.

“In essence, photography requires an acute awareness of the world and a readiness to respond to fleeting moments, while painting allows for deeper manipulation and reworking. Yet, with digital photography and editing tools, modern photographers now have more control, blurring the lines between taking and making an image,” Angel, one of the maintenance workers at the college, said in passing. He has a point.

The line between painting and photography has undeniably blurred due to advancements in digital technology and post-processing techniques. While traditional photography was largely about capturing a moment as it was, modern photographers have access to tools that allow them to manipulate images in ways that were once exclusive to painting.

In the past, photography was seen as a means of truthfully documenting the world. Today, with software like Photoshop and Lightroom, photographers can change colors, remove objects, add elements, and even merge multiple images, making the final result more of a constructed image rather than a captured one.

Digital tools -- God bless them - allow photographers to adjust lighting, contrast, and texture in ways that mimic painting techniques. For example, a portrait photographer can digitally paint over skin, enhance shadows, and completely reshape an image to match their artistic vision, much like a painter with a brush.

And what about AI? It can generative fill features, photographers can create images that may never have existed in real life. This ability to generate, rather than just capture, further blurs the distinction between photography and traditional image-making.

In the past, painters constructed their images from scratch, while photographers relied on reality. Today, many photographers spend more time in post-production than in the act of taking the picture itself. This means they are no longer just taking photographs—they are actively creating images in ways that were once the domain of painters and digital artists.

But… despite digital manipulation, one key distinction remains: photography is still often rooted in reality. A photographer captures a moment in time that actually existed, then may choose to enhance or modify it. Unlike painting, where every detail must be built from nothing, photography starts with the world as it is and works from there.

So, while the line between painting and photography has blurred with modern technology, a core difference remains: painting allows for infinite imagination and control, whereas photography—at least in its purest form—depends on discovering moments in the real world. However, today’s photographers often find themselves combining these two artistic traditions, using digital tools to blend reality with creative vision in a way that would have been unthinkable when Cartier-Bresson coined the idea of the "decisive moment."

But I digress.

Here are the five key elements John Scarkowski explores in “The Photographer’s Eye”:

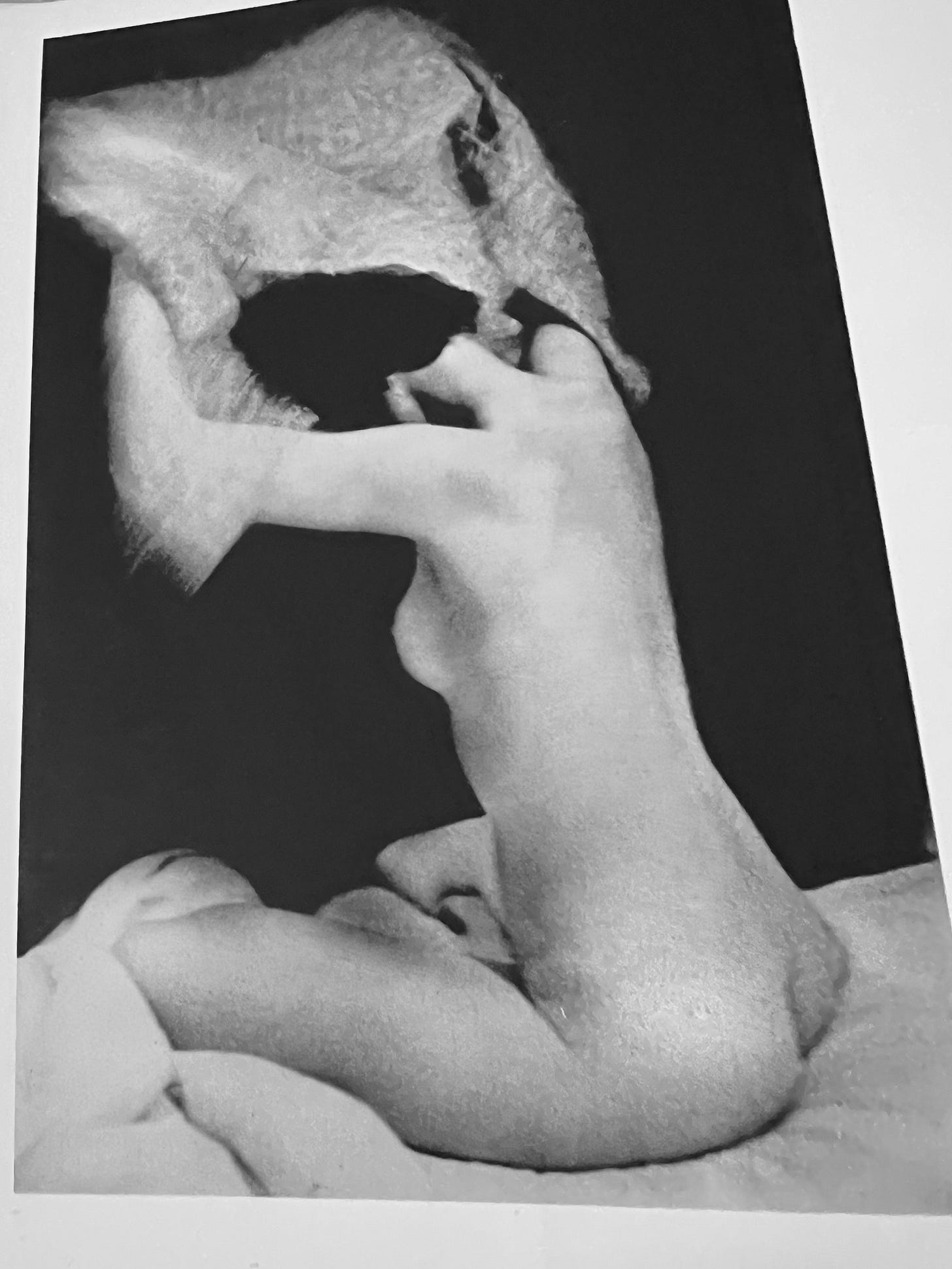

The Thing Itself: Photography captures reality and guarantees the existence of what is photographed. It transforms subjects into "things" within the frame, giving significance to even empty spaces.

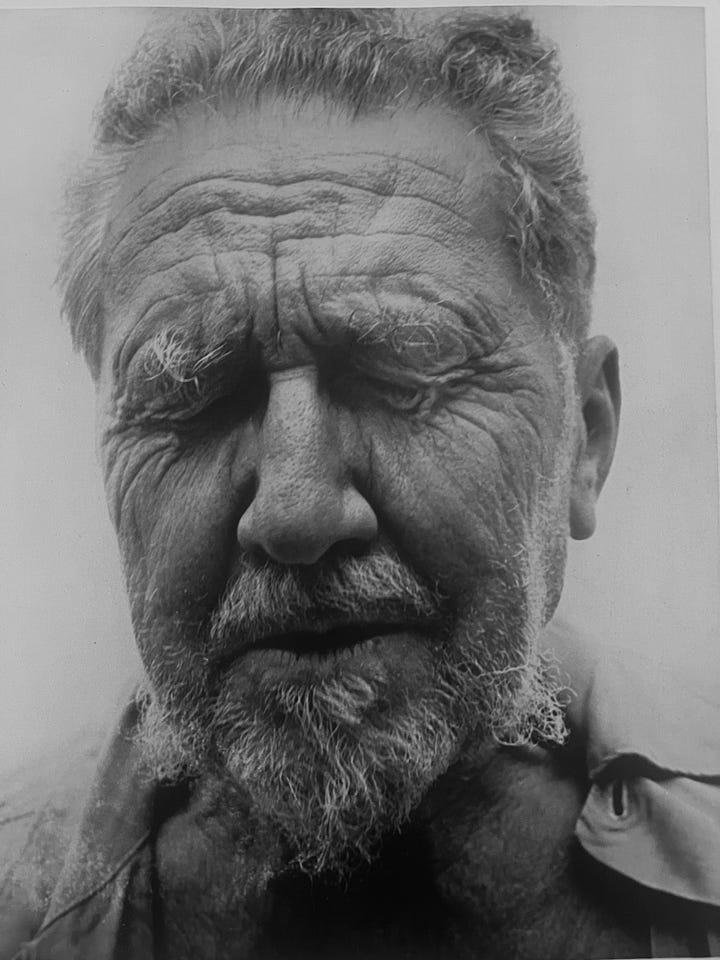

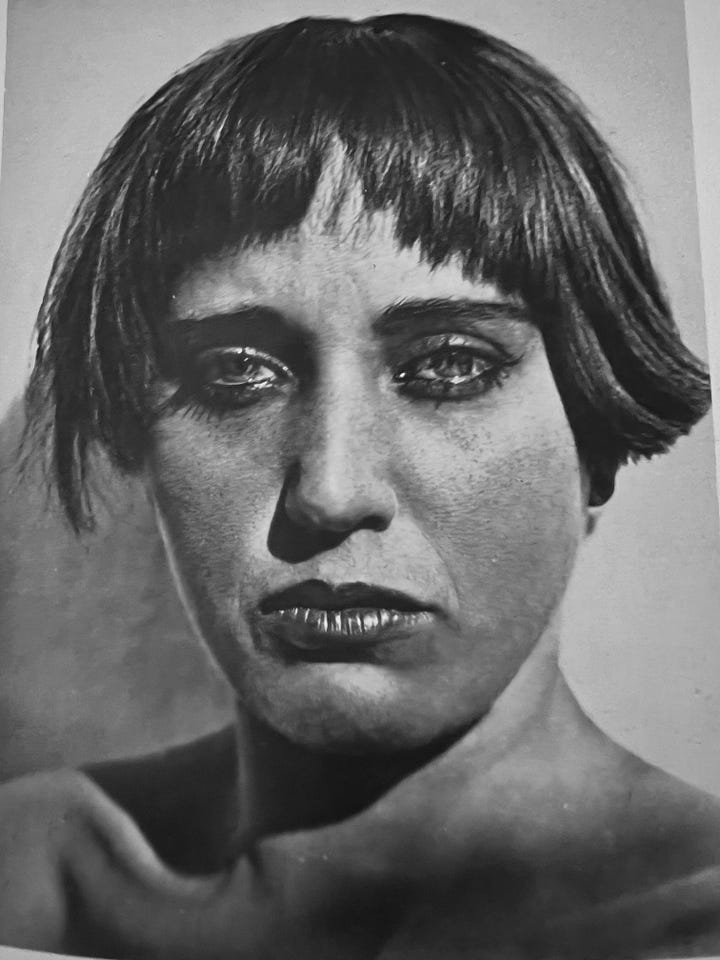

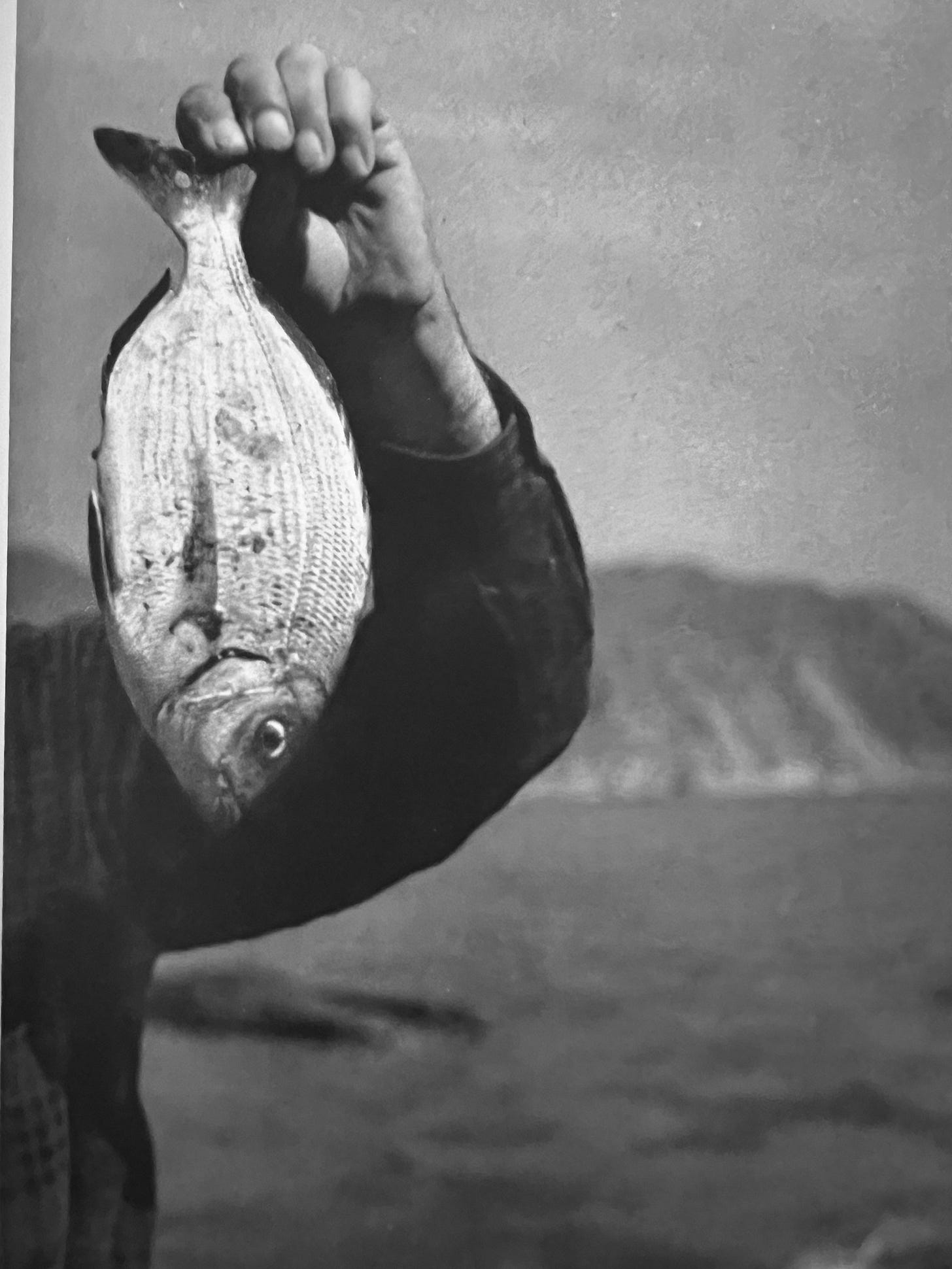

The Detail: Photographers capture fragments of truth rather than complete narratives. By focusing on specific details, they can reveal deeper meanings and highlight overlooked elements.

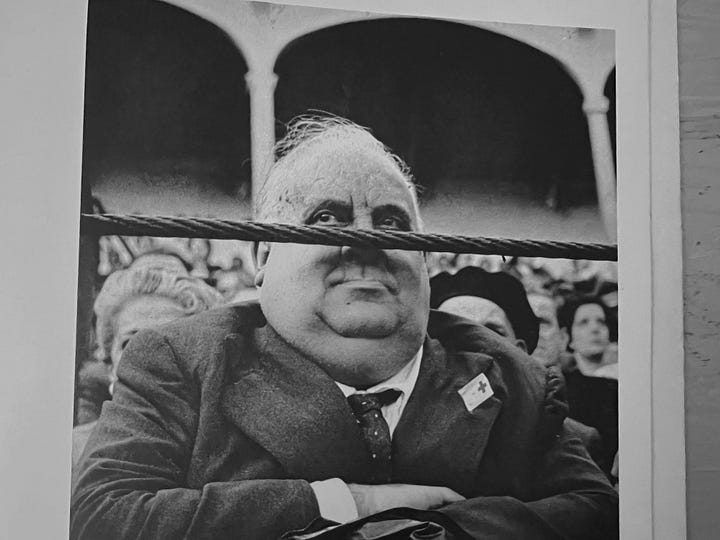

The Frame: Photography is an art of selection. The edges of the picture dictate its content, and the photographer chooses what to include or exclude by adjusting camera position and angle.

Time: Photographs are time exposures that capture specific moments. As photographic technology improved, photographers began experimenting with capturing fast-moving objects.

Vantage Point: The clarity and impact of a photograph depend on the photographer's chosen perspective. Unexpected vantage points can transform ordinary subjects into dramatic and exciting images.

Szarkowski's approach breaks from traditional compositional rules, encouraging photographers to experiment and find new ways of seeing. Photography's history is not linear but a "centrifugal" growth, with its meaning continually evolving through our progressive discovery of the medium.

Thanks for reading and being a subscriber.

’Til next time.

ak

Essential reading! Interesting to see which examples you chose from the book (and, for me, where we overlap: https://neilscott.substack.com/p/the-photographers-eye-by-john-szarkowski)

This meditation on the photographer’s gaze is as much about seeing as it is about being seen. You articulate that sacred tension between observer and subject—how a single frame can hold both intimacy and distance, reverence and revelation. A reminder that the most powerful images aren’t taken, but received.