Peculiar Habits of Famous Russian Writers

Other Stuff

ALEXANDER PUSHKIN, lost in thought, drew portraits in the margins of his drafts - his own, his friends', and acquaintances'. While working on "Eugene Onegin," he sketched female feet, boats, horses, and the figure of a departing woman in the margins, for these drawings helped him concentrate.

A lover of lemonade, Pushkin would instruct his servant to always have a pitcher of lemonade in front of him while he worked. However, the lemonade of Pushkin's time was different from today's version: it was lemon juice mixed with burnt sugar and mineral water. Pushkin made his characters also appreciate this refreshing drink. Herman from "The Queen of Spades" drank lemonade, and in "The Stationmaster," the girl Dunya prepared it for her father.

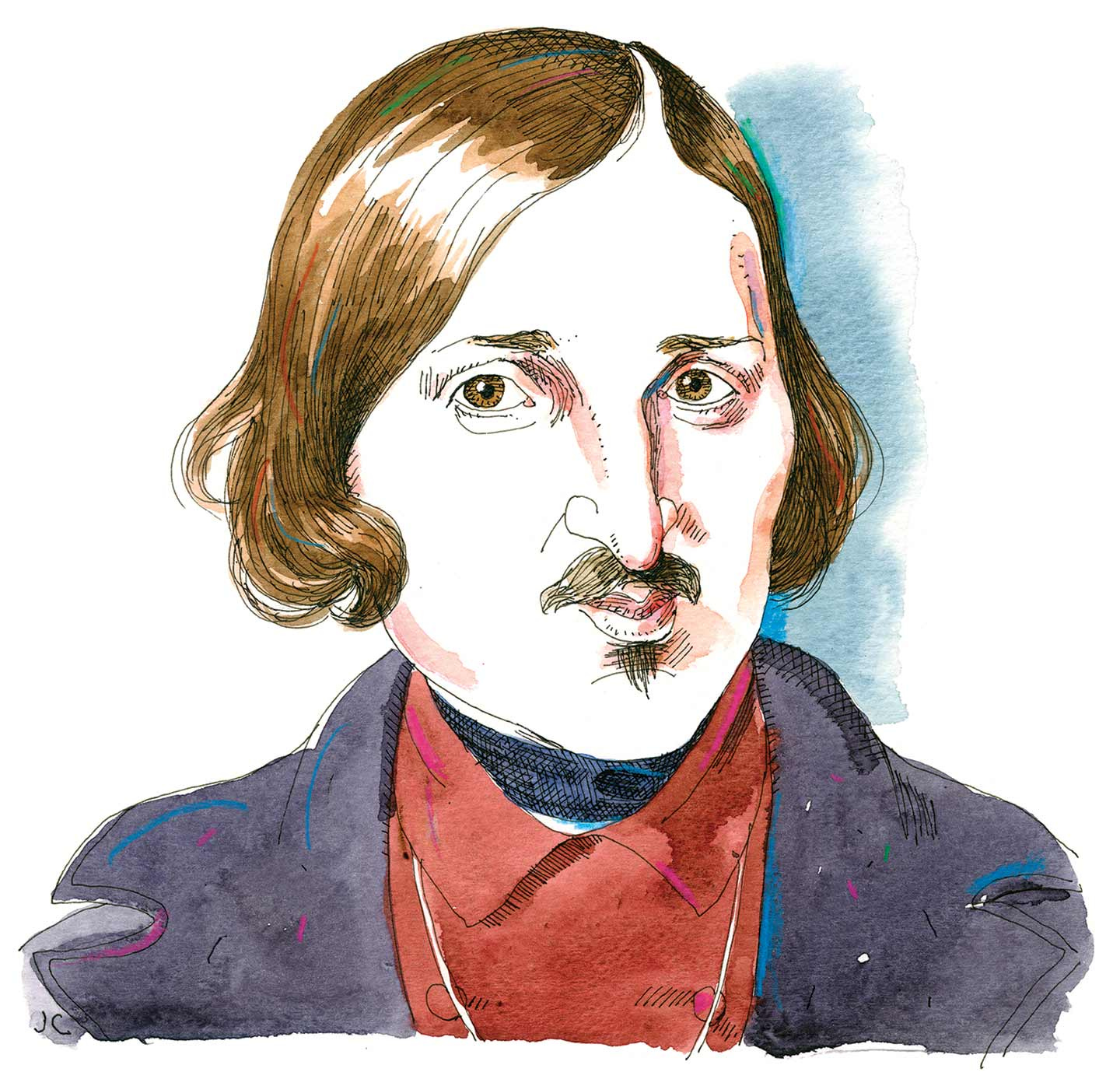

NIKOLAI GOGOL worked standing up and slept sitting down. In his youth, he suffered from encephalitis, and its complications included periodic fainting spells, after which the writer fell into a deep sleep. Once, his body stiffened to the point that those around him thought he had died in his sleep. Gogol feared that he might be mistaken for dead and buried alive, so he slept in a chair to stay more alert.

During his work, he would roll dozens of bread crumbs into balls; these nervous, twitchy finger movements helped him concentrate. And if inspiration didn't come, Gogol would place a pitcher of cold water in the farthest rooms of his house. Historian Mikhail Pogodin recounted, "Gogol walked from one room to another and every ten minutes drank a glass. Gogol walked very fast and somehow jerkily, producing such a wind that the stearin candles melted, much to the chagrin of my thrifty grandmother. And when Gogol got too carried away, my grandmother, sitting in one of the rooms, would shout to the maid, 'Grusha, oh Grusha, bring a warm shawl, Talienets (as she called Gogol) is blowing so much wind, such passion.' 'Don't be upset, old lady,' Gogol would good-naturedly say, 'I'll finish the pitcher, and that'll it.'"

FYODOR DOSTOEVSKY liked to recite his texts out loud. Once, he moved into an empty summer house belonging to acquaintances. He worked, as usual, during the night. The writer's niece later recounted how a frightened servant rushed to the owners and reported that they should go straight to the police as the writer had "planned to murder someone." Supposedly, Dostoevsky didn't sleep at night, pacing between rooms and reasoning with himself about suicide. During this time, the writer was working on "Crime and Punishment," contemplating Raskolnikov's intention.

Fyodor Mikhailovich would mercilessly destroy drafts, but he treated the finished manuscript with great care. He never sent it to the publisher with a messenger, fearing that they might lose the final version, into which he had put much effort. Instead, he would carry it himself.

ANTON CHEKHOV had the ability to concentrate in any situation: "In the next room, a baby of some relative who had come to visit is crying; in another room, a father reads aloud to the mother... Someone wound up a musical box, and I hear 'Elena the Beautiful.'"

Even the presence of strangers didn't disturb Chekhov. "Wait, I'll finish soon," he would say to a friend who dropped in for a chat, and calmly continued writing with a delicate quill.

The actor Svobodin, a close friend of the writer, once noted in a letter: "You see, Schiller, while working, liked to have rotten apples lying next to him and in the drawer. But you absolutely need people singing and making noise above you, while Michel (Chekhov's younger brother, Mikhail) is smearing the stove tiles behind your back... and the room smelling not of rotten apples, but of Michel's paint."

Chekhov once observed that the intelligent person loves to learn, while the fool loves to teach.

LEO TOLSTOY didn’t believe in sharing habits, especially writing habits. But he did believe that was impossible to teach one how to become a writer, and was annoyed when authors asked him to share secrets of the trade. In 1895, he replied to an author: “…I won’t answer your questions, or rather interrogation, about writing, because they are all empty questions. The one thing I can say to you is to try as hard as you can not to be a writer, or only to be one when you can no longer help being one.” And he suggested to another author, “You should only write when you feel within you some completely new and important content, clear to you but unintelligible to others, and when the need to express this content gives you no peace.”

VLADIMIR NABOKOV worked like today's Hollywood screenwriters who jot down three-minute scenes on index cards and then shuffle them this way and that. Nabokov found his best writing flow on catalog cards. In the days before computers, he could flip the deck, easily rearrange paragraphs, and spin plotlines anew. The finished book fit into a shoebox.

This habit began with "Lolita." During his first trip to America, Nabokov discovered that the quietest place in the country was the back seat of his car. There, he sat at night, using the shoebox as a small table, and filled it with index cards. When he finished another piece, his faithful wife, Vera Slonim, would step in. An impressive woman, she was a marksman, skilled boxer, and always carried a small Browning pistol in her pocket. Vera would sit at the typewriter and retype the book from the cards, beginning to end.

His spouse was living proof that the Nabokov who wrote "Lolita" was not a maniac or a pedophile; he married Vera when she was 25 years old and loved her passionately throughout his life.

JOSEPH BRODSKY hated discussing his writing process, but he thoroughly enjoyed offering advice on how to live life and how to prevent it from slipping away. In his now famous commencement address at University of Michigan in 1988, he says this:

”I think it will pay for you to zero in on being precise with your language. Try to build and treat your vocabulary the way you are to treat your checking account. Pay every attention to it and try to increase your earnings. The purpose here is not to boost your bedroom eloquence or your professional success — although those, too, can be consequences — nor is it to turn you into parlor sophisticates. The purpose is to enable you to articulate yourselves as fully and precisely as possible; in a word, the purpose is your balance. For the accumulation of things not spelled out, not properly articulated, may result in neurosis. On a daily basis, a lot is happening to one’s psyche; the mode of one’s expression, however, often remains the same. Articulation lags behind experience. That doesn’t go well with the psyche. Sentiments, nuances, thoughts, perceptions that remain nameless, unable to be voiced and dissatisfied with approximations, get pent up within an individual and may lead to a psychological explosion or implosion. To avoid that, one needn’t turn into a bookworm. One should simply acquire a dictionary and read it on the same daily basis — and, on and off, with books of poetry.”

MARINA TSVETAEVA’s life in many ways resembled her poems: sharp and unexpected transitions, long pauses, vivid and sensual moments that could be sensed in a single breath. Each distinct period of her life was a complete poem with its own rhythm and rhyme.

She had a complex and difficult marriage with the poet Sergey Efron, a passionate love affair with a woman, and was emotionally distance from her children. Marina Tsvetaeva's life was multi-faceted and it cannot be described in a single article.

Joseph Brodsky called Marina Tsvetaeva the greatest poet of the 20th century. And not just among Russians, but among all. I will only add that she also had the most difficult, inhumanly difficult fate. However, throughout her life, her main companions remained her own habits.

She didn't wear glasses and lived in her own world. Tsvetaeva was severely nearsighted, yet she refused to wear glasses. She preferred to see the world her way: slightly blurred images of people, an unclear sun. When she needed to see a detail or read something, she used a lorgnette. Tsvetaeva didn't give away her "secret": she didn't squint or lean in. She continued to stare with a penetratingly glassy gaze.

Her handshake was long and firm. Firm handshake. She was unfamiliar with the gentle, light gesture of introduction. Tsvetaeva shook hands like a lumberjack, which is something she learned from the poet Maxim Voloshin (1877 – 1932), which she admitted herself. She had to walk a lot.

Tsvetaeva's daughter Ariadna wrote that the her mother feared many urban elements. For example, heights, tall buildings, approaching crowds. Tsvetaeva experienced fear of cars, escalators, elevators. That's why she was forced to walk a lot because among the modes of public transport, she could only use trams and occasionally the metro.

24 Poems of Marina Tsvetaeva

______________

‘Til next time,

ak

Great stuff. Are there any famous female Russian writers?

I'll have them both up.

Believe it or not, I have never read any Chekhov or gone to any of his plays, anywhere. They were planning to stage 'Uncle Vanya' near here at a local playhouse but the flooding nixed that for now.